LI CEO Dan Cook, President Merrick Denton-Thompson, Honorary Secretary James Lord and member David Booth spoke with leading landscape practitioners and thinkers over the course of a week in November 2017

In June, three prominent Chinese academics, including Xiangrong Wang, Professor, Vice-Dean and Doctoral Supervisor at Beijing Forestry University’s School of Landscape Architecture, attended the Landscape Institute (LI) annual conference. Following this, the University obtained a government grant to fund and host a study trip for four guests from the LI. The visit took place from 13 to 18 November 2017.

Landscape education in Beijing and beyond

Beijing Forestry University takes on approximately 250 landscape undergraduate and postgraduate students per year. It is currently home to over 1,000 – more students, in fact, than now study forestry. Reflecting the importance of women in Chinese landscape architecture, approximately 70% of students are female.

Higher education in China encourages diversification. There is a strong appetite to obtain postgraduate qualifications in new, often overseas, institutions, before returning home with fresh knowledge. We see the benefit of this in the UK; a full fifth of our international landscape students are from China alone.

Indeed, course leaders at Beijing Forestry University think highly of UK landscape education, and encourage many of their students to pursue postgraduate qualifications in the UK. There are a number of areas where the Chinese and UK models overlap – and areas where collaboration could facilitate growth on both sides.

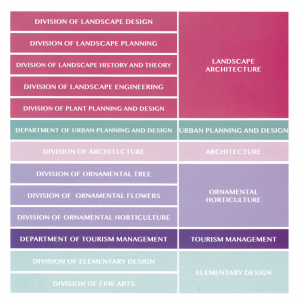

In Beijing, subject areas such as landscape engineering and ornamental horticulture are more developed. Additionally, tourism management falls under the remit of landscape education in Beijing. Given the importance of tourism to landscape managers in the UK, including those of National Parks and AONBs, this is something to bear in mind when engaging with this sector.

Conversely, technical areas including visual impact assessments and landscape character assessments are more developed in the UK. This is in large part due to the lack of regulatory oversight in Chinese landscape practice. The landscape profession in China is relatively infant, and there is no licensing or accreditation body.

Clearly, given the parallels between UK and Chinese landscape practice, the potential for knowledge sharing, and the extant academic relationships, there are many opportunities for the LI to explore internationally. The LI Board of Trustees will shortly consider proposals from our CEO to overcome barriers to inclusivity, and make our Chartership and accreditation syllabuses more open, flexible and internationally relevant.

A cultural exchange

Profession Xiangrong Wang invited Merrick to speak to landscape students at Beijing Forestry University. Noting the many differences between the UK and China, Merrick nevertheless observed the shared challenges of sustainability, resilience, urban expansion, health and wellbeing, and biodiversity that manifest themselves in both countries on very different scales. He discussed the current shape of the UK landscape profession and the diversity of its specialisms beyond design, noting that ‘[while] the process of design touches less than 1% of the land at any one time … the remaining 99% is being transformed all the time through management processes’. An enthusiastic Q&A followed the talk.

Read a transcript, and Chinese translation, of Merrick’s talk. (PDF, 656 KB.) Our thanks to Angie Yin for translating this speech.

A group of students remained the LI cohort’s ‘inspiring, knowledgeable and thoughtful’ guides throughout the week.

‘Though all studying in Beijing,’ Dan said, ‘the group hailed from across the length and breadth of China. We discovered a lot about the country’s regional and cultural diversity. It was clear that all of the students are truly passionate about landscape; they’re smart, inquisitive, and always thinking about the bigger picture.’

Chinese landscape practice

On day two, the delegation met principals of the Chinese Society of Landscape Architecture (CHSLA) and landscape industry leaders. Its president, Chen Xiaoli, is a former urban land planner who has been instrumental in establishing the landscape profession in China.

Though a member of IFLA, CHSLA is more interest group than licensing body. Nevertheless, it shares many common responsibilities with other member organisations. The challenges China faces include rapid urbanisation, environmental degradation, threats to biosecurity and resilience, and deforestation. The CHSLA aims to organise and empower members to tackle these issues, and to demonstrate to legislators the value of professional intervention.

Also present were members of the Beijing branch of the China Academy for Urban Planning and Design (CAUPD). China’s leading planning policy advisor, CAUPD employs approximately 90 landscape experts out of a total 550 staff. Its Beijing members discussed projects including wetland restoration, flood alleviation and disaster relief, urban redevelopment, urban green space planning, and heritage conservation.

Visit the members’ area to see the CAUPD presentation. (Login required.)

In China, the concept of national parks is in its infancy. China’s first formally designated national park, Zhangjiajie National Forest Park, was established in 1982 – over a century after Yellowstone. Due to the rapid industrialisation of China’s landscape in recent decades, the government has placed greater emphasis on creating parks to protect biodiversity and enhance environmental quality. Economic growth has also improved disposable income and vacation times, which has bolstered the country’s ecotourism industry. This is another area where standards and knowledge sharing with the UK could be of potential benefit.

Adaptive re-use

On one of many site visits in the city, our visitors also saw how the repurposing of industrial infrastructure has helped to tackle Beijing’s poor air quality.

The Chinese capital suffers from an acute air pollution problem. Its scale and complexity is such that it may be impossible to fully reverse, but some measures have had a positive impact.

The Dashanzi Art District, or 798 Art Zone, is a thriving arts and design community housed in a complex of decommissioned military factories. Rather than destroy and replace the factories, authorities adapted the existing infrastructure for new purposes, including art and design, creative services, and retail.

Beijing is also building a 70-kilometre green corridor that will surround 18 parks and connect 26 hutongs. And by building green patches around railway lines, authorities aim to further improve ventilation in the city.

With air pollution worsening in the UK’s major cities, there is a lesson here for our planners and developers. By adapting, rather than destroying, our existing infrastructure, we can give our cities new ‘green lungs’. Projects such as Connswater Community Greenway in East Belfast already show on a smaller scale how adaptive re-use can benefit communities by creating vibrant, healthy and accessible land.

Urban planning and regeneration

Many neighbourhoods in Beijing and other northern Chinese cities comprise high-density, low-rise residential areas called hutongs. Over 800 years old, hutongs are architecturally unique and culturally important. Yet, since the mid-20th century, Beijing has seen a large number demolished to make way for wide boulevards and high-rise complexes.

Nowadays, many hutongs are protected. Another stopping point for our visitors was the Shijia Hutong Museum. Funded by the Prince’s Charities Foundation as well as local government, the museum preserves some eight centuries of town planning history.

Many such initiatives in Beijing are government-instigated. The Dashilar Project, another Beijing initiative, is run by Beijing Dashilar Investment Limited – an NGO established as a platform for local government and stakeholders to collaborate on infrastructure and non-profit investment on a municipal level. The strategy holds that ‘smaller, family run business does not need to conflict with investment’. This holistic attitude has, interestingly, led to some very granular solutions, focusing on microregeneration, urban curation and mediation. Through a ‘node approach’, the scheme offers both subsidies for renovation work and rental discounts to local businesses. This approach emphasises ‘soft infrastructure’ – the social, cultural and economic aspects of an area.

In stark contrast to China, the majority of land in the UK is in private ownership. And yet, many landscape schemes in the UK originate in the public or third sector. (Over 70% of the 2017 LI Award-winning schemes had public or third sector clients.)

However large the challenges Beijing has to overcome, the city shows us that even in a relatively short period of time, an interconnected and multidisciplinary approach can deliver substantial benefits. It suggests that by cultivating relationships with public sector clients, we in the landscape profession could better demonstrate the true value and impact of our work on the largest possible scale.